The International Ez Zantur Project

- Welcome to the International Ez Zantur Project

- Outline of the International Ez Zantur Project

- Selected bibliography of the International Ez Zantur Project

- Preliminary Report on the 2002 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2001 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2000 Season

- I. Introduction

- II. Ez Zantur IV: The Nabataean mansion

- III. Ez Zantur IV: Position and architectural features of the main entrance

- IV. Ez Zantur IV: Courtyard 28 and rooms 35–37

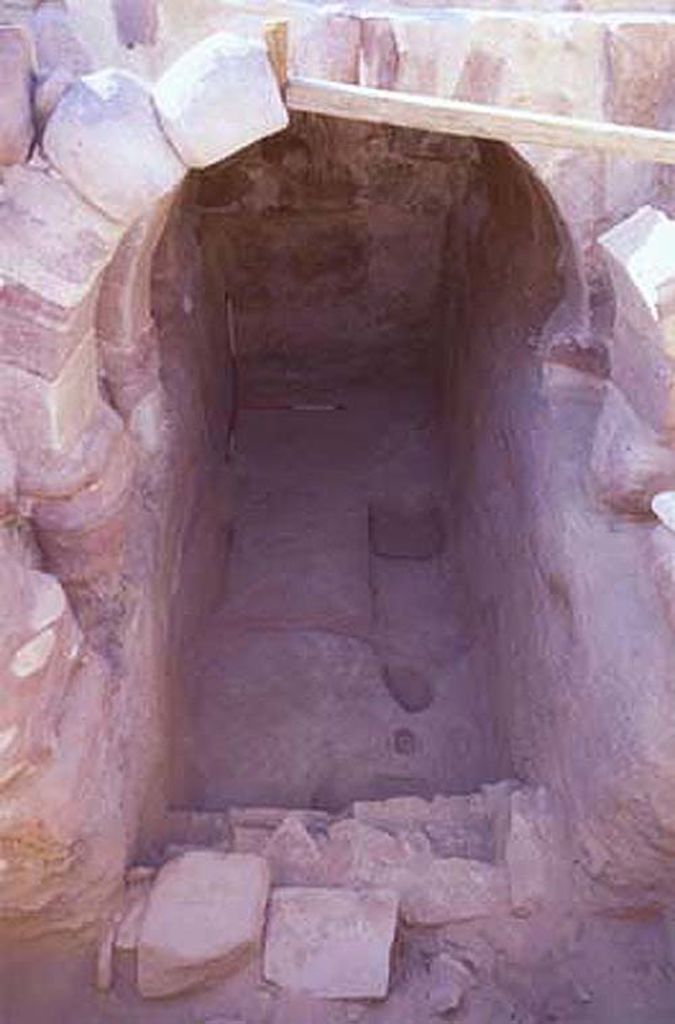

- V. Ez Zantur IV: The substructures of room 17

- VI. Ez Zantur IV: Rooms 38–40

- VII. Ez Zantur IV: An eye idol found in room 30

- VIII. Ez Zantur IV: Another type of glass lamp from ez Zantur

- Preliminary Report on the 1999 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 1998 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 1997 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 1996 Season