The International Ez Zantur Project

- Welcome to the International Ez Zantur Project

- Outline of the International Ez Zantur Project

- Selected bibliography of the International Ez Zantur Project

- Preliminary Report on the 2002 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2001 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2000 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 1999 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 1998 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 1997 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 1996 Season

- I. Introduction

- II. Ez Zantur IV: Soundings 1 and 2

- III. Ez Zantur IV: Chronological remarks

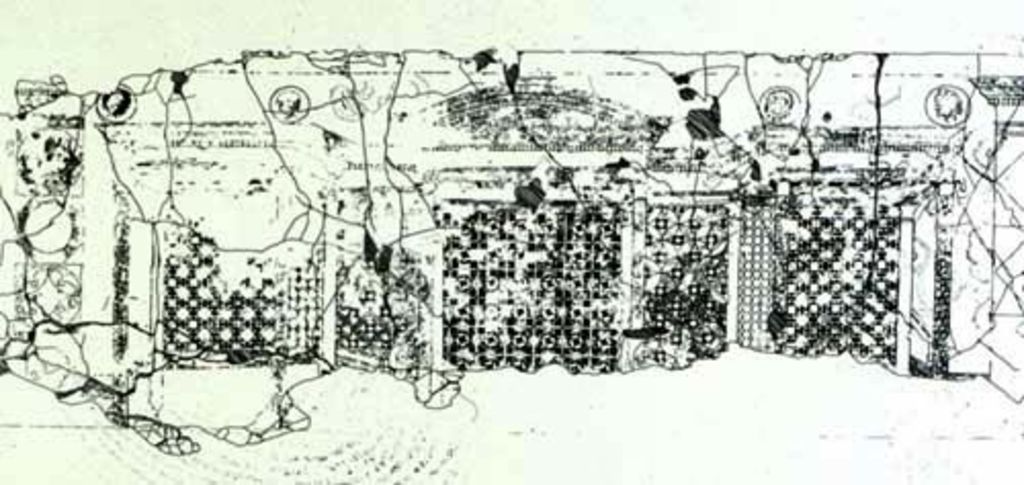

- IV. Ez Zantur IV: Wall decoration in room 1

- V. Ez Zantur IV: Wall decoration in rooms 2 and 3

- VI. Ez Zantur I: The workshop area

- VII. Ez Zantur III: The northeastern area

- VIII. Ez Zantur IV: Mosaic glass from ez Zantur

- IX. Ez Zantur IV: An engraved gem depicting Athena as Palladion from ez Zantur