The International Khubta Tombs Project

- Welcome to the International Khubta Tombs Project

- Outline of the International Khubta Tombs Project

- Selected bibliography of the International Khubta Tombs Project

- Preliminary Report on the 2010 Season

- I. Acknowledgments

- II. Introduction

- III. Fieldwork Strategy

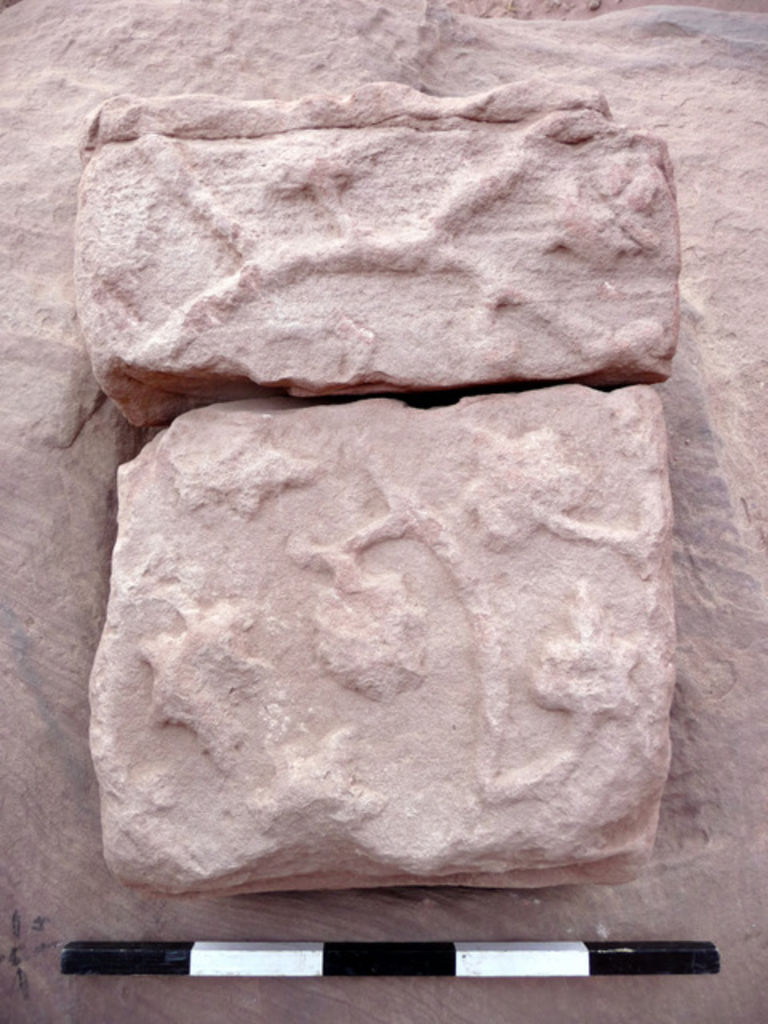

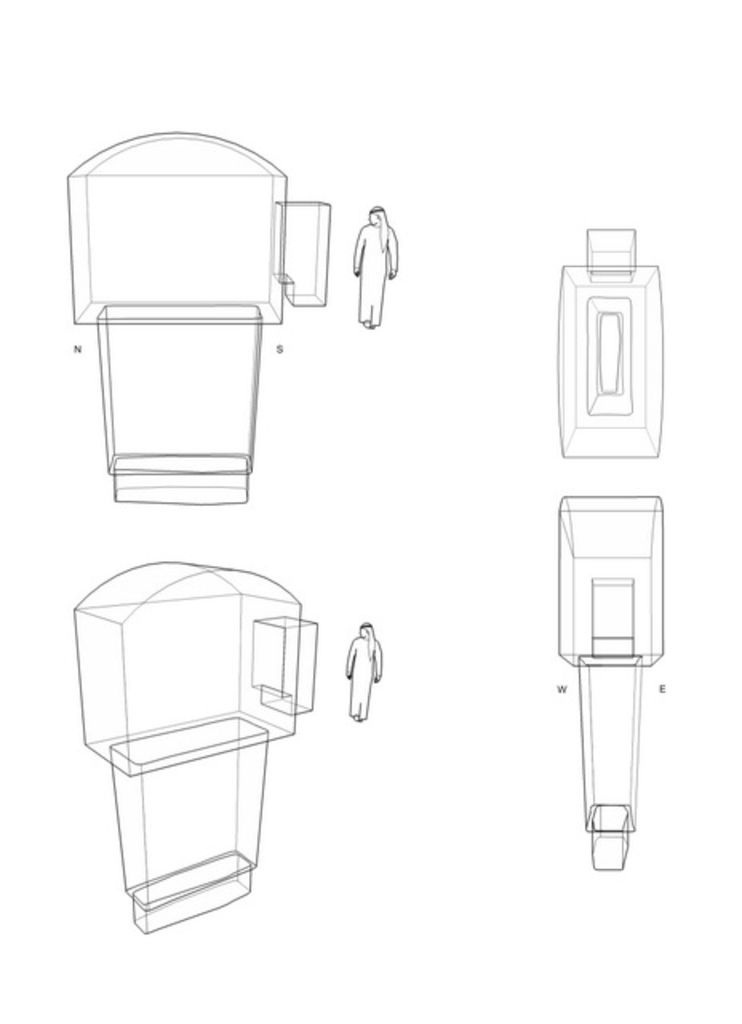

- IV.a. Preliminary Results: Tomb 779 – Exterior (Sector A)

- IV.b. Preliminary Results: Tomb 779 – Interior (Sector D)

- V.a. Preliminary Results: Tomb 781 – Exterior (Sector B)

- V.b. Preliminary Results: Tomb 781 – Interior (Sector C)

- VI. Concluding Remarks and Future Work