The International Wadi Farasa Project

- Welcome to the International Wadi Farasa Project

- Outline of the International Wadi Farasa Project

- Selected bibliography of the International Wadi Farasa Project

- Preliminary Report on the 2009 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2007 Season

- I. Introduction and acknowledgments

- II. Northern portico

- III. NE-corner of complex and entrance to the huge triclinium

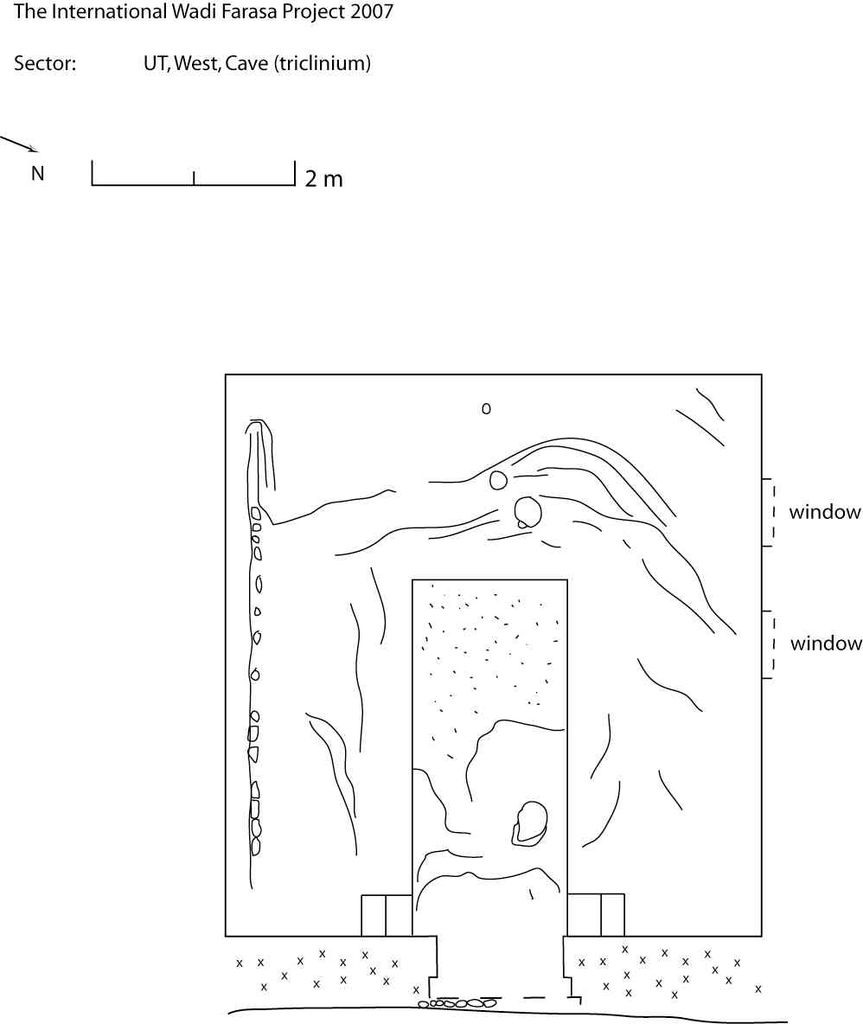

- IV. Rock-cut room at the western corner of the complex

- Preliminary Report on the 2006 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2005 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2004 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2003 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2002 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2001 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2000 Season