The International Wadi Farasa Project

- Welcome to the International Wadi Farasa Project

- utline of the International Wadi Farasa Project

- Selected bibliography of the International Wadi Farasa Project

- Preliminary Report on the 2009 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2007 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2006 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2005 Season

- I. Introduction and acknowledgments

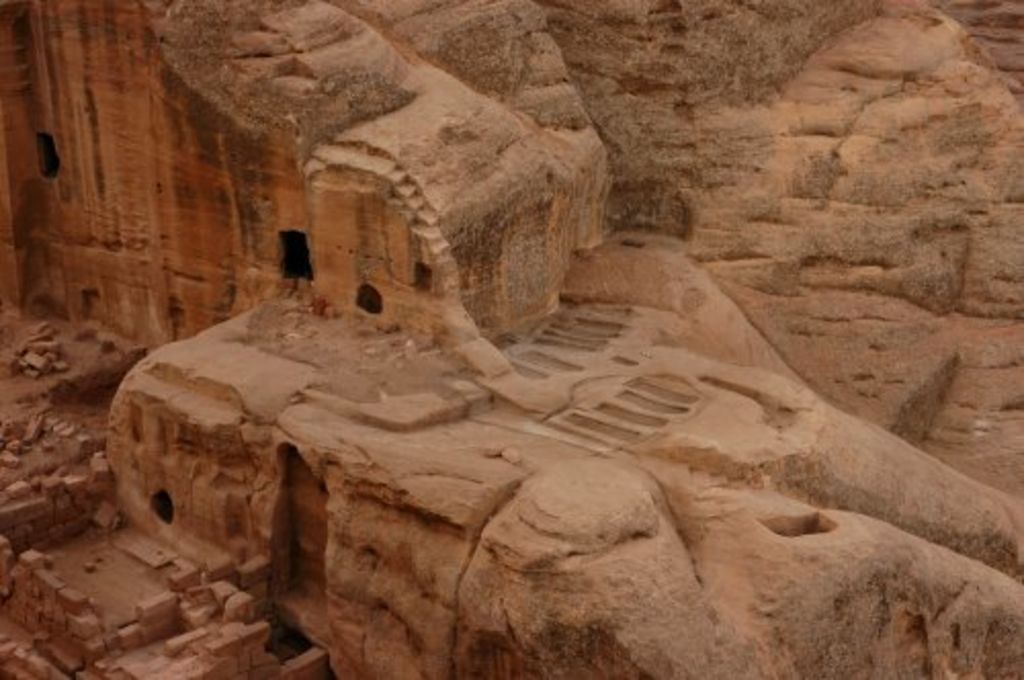

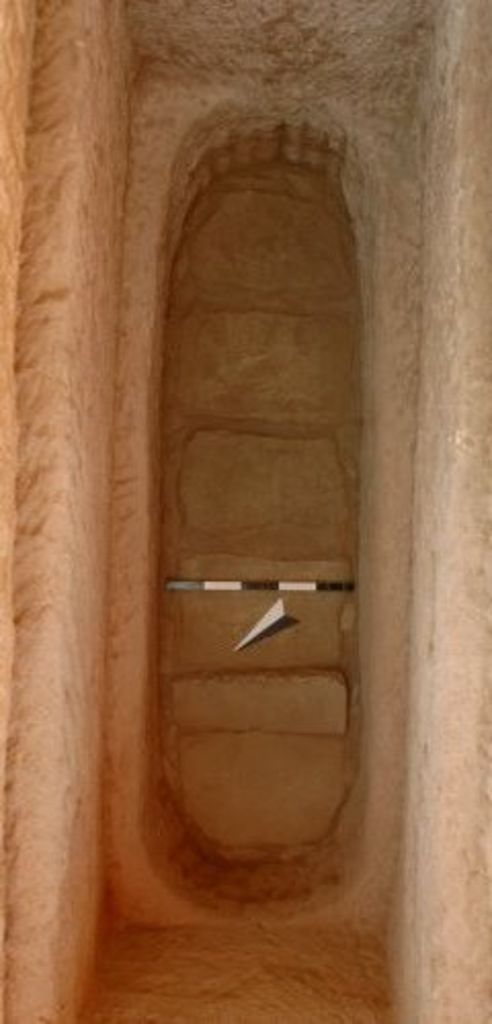

- II. Northeast-corner of the complex

- III. Northern portico

- IV. Western corner of the complex

- Preliminary Report on the 2004 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2003 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2002 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2001 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2000 Season