The International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Welcome to the International Umm al-Biyara Project

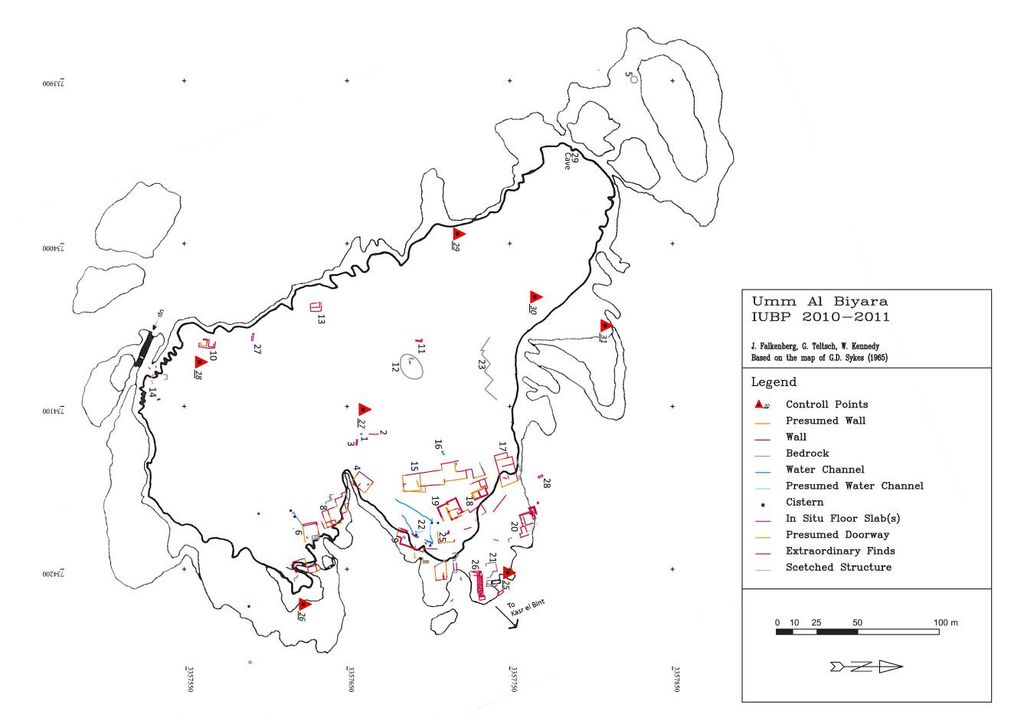

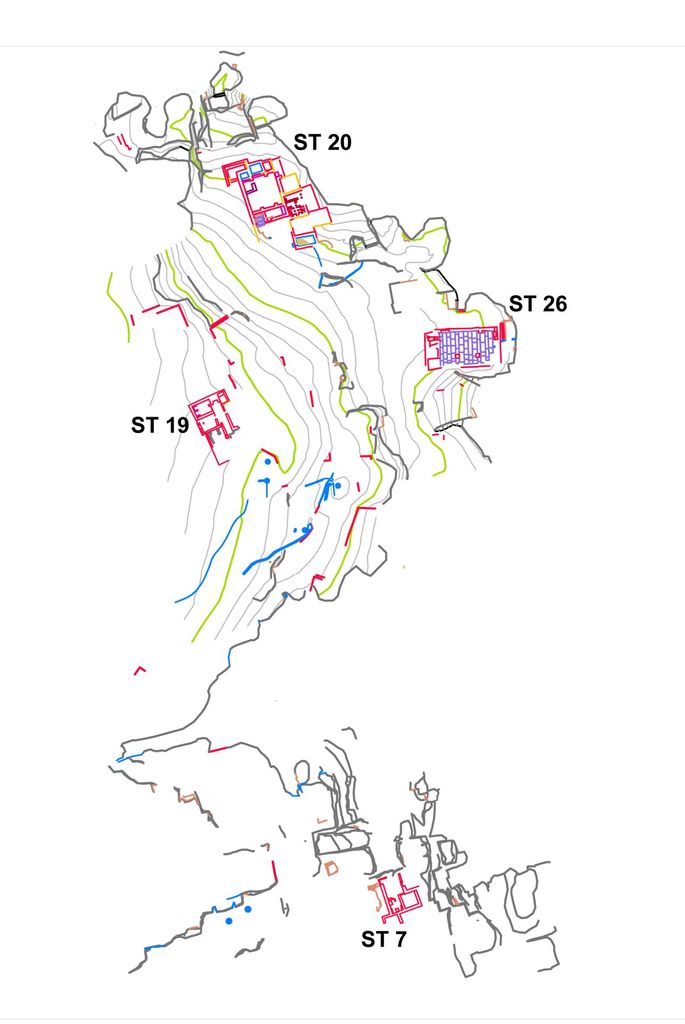

- Outline of the International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Selected bibliography of the International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Preliminary Report on the 2014 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2013 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2012 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2011 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2010 Season