The International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Welcome to the International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Outline of the International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Selected bibliography of the International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Preliminary Report on the 2014 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2013 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2012 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2011 Season

- I. Acknowledgments

- II. Introduction

- III. 2011 excavations – a. structure 10

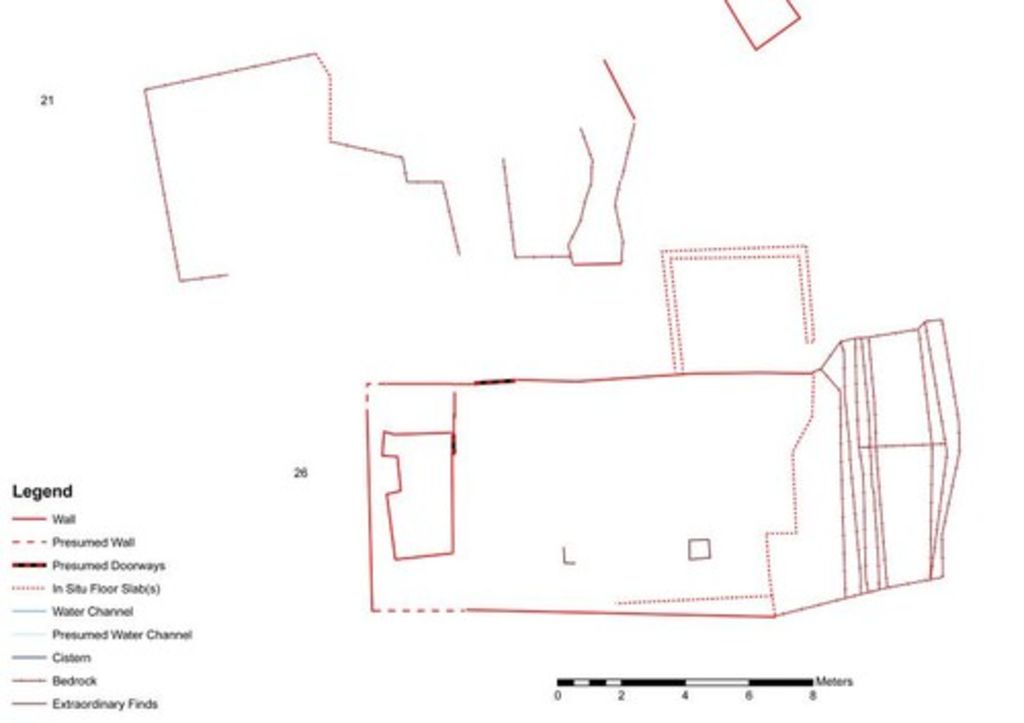

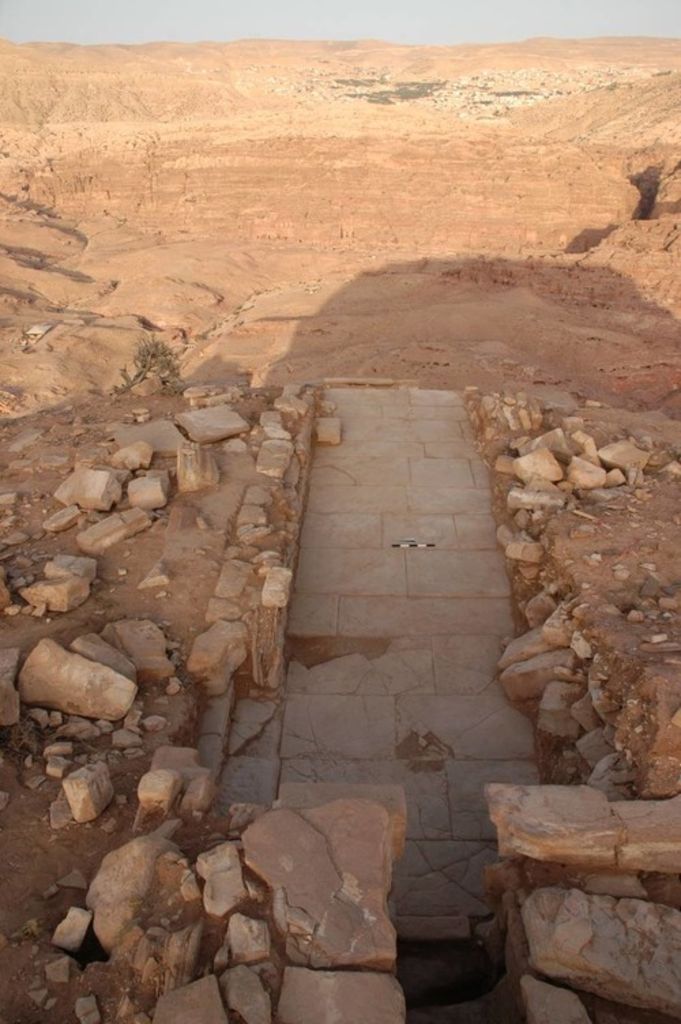

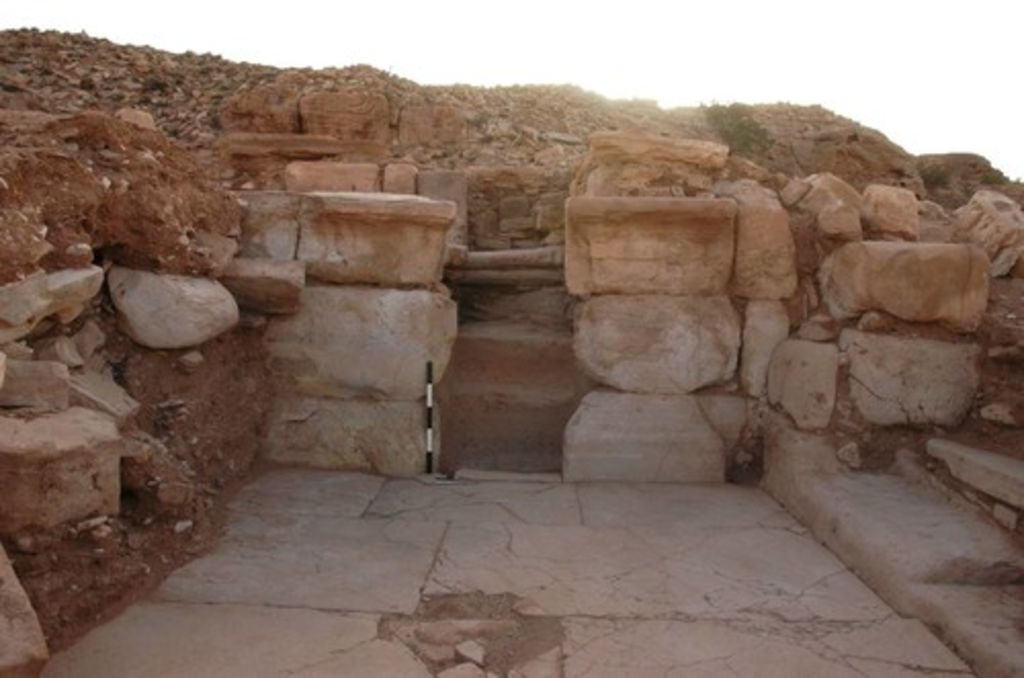

- III. 2011 excavations – b. structure 26

- III. 2011 excavations – c. structure 20

- IV. Conclusions

- Preliminary Report on the 2010 Season