The International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Welcome to the International Umm al-Biyara Project

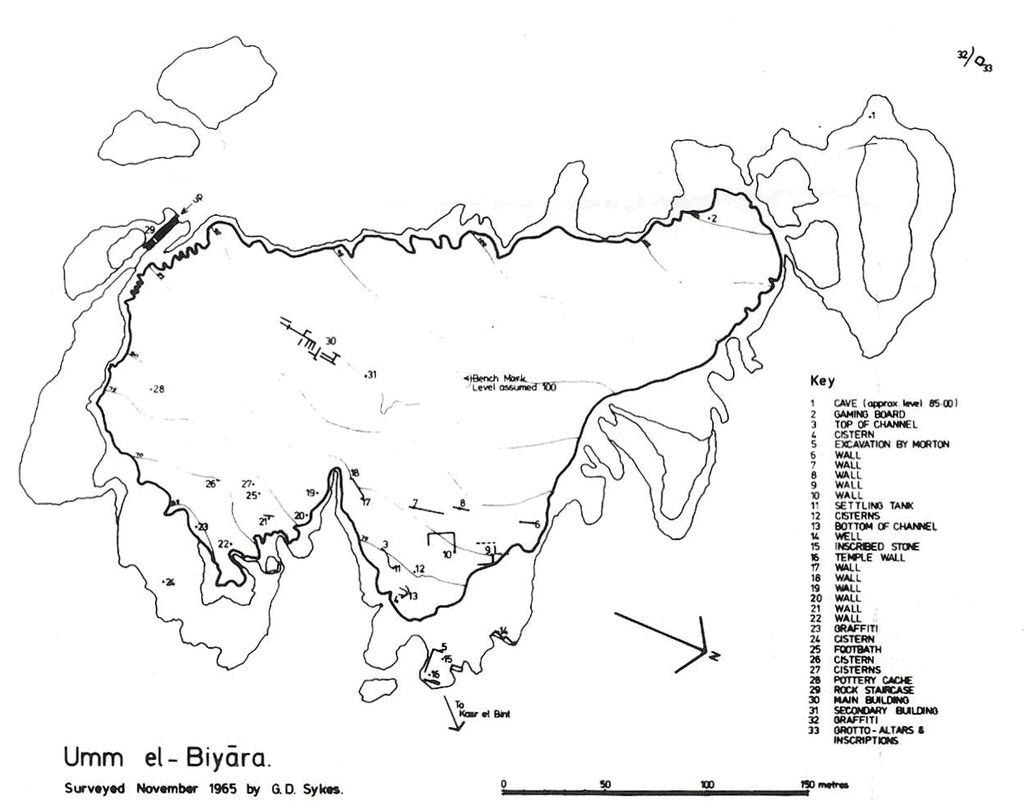

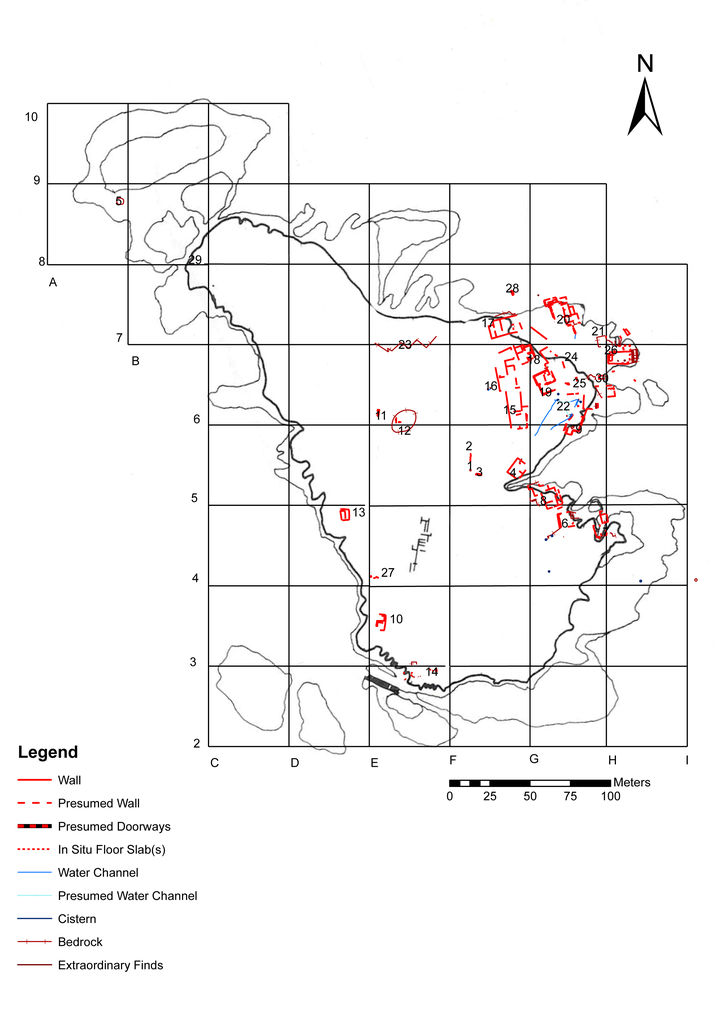

- Outline of the International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Selected bibliography of the International Umm al-Biyara Project

- Preliminary Report on the 2014 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2013 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2012 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2011 Season

- Preliminary Report on the 2010 Season

- I. Acknowledgments

- II. Introduction

- III. First Results – a. General observations

- III. First Results – b. A watchtower?

- III. First Results – c. A luxurious bathing installation

- III. First Results – d. A room with a view

- III. First Results – e. Water management

- III. First Results – f. Parallels and interpretation

- IV. Conclusions and perspectives